“She believed cemeteries held the stories that history books could not always document; they were the overlooked, underused classrooms beneath our feet . . .”

A barren lot

Nestled in Southeast Portland, Lone Fir Cemetery is one of Portland’s oldest continuously used cemeteries as well as the city’s second largest arboretum, with more than 700 trees representing 67 species. Delightfully shady in the summer and spectacular in the fall, Lone Fir is a wonderful destination for a birdsong-filled wander amongst interesting and ornate gravestones dating as far back as 1846.

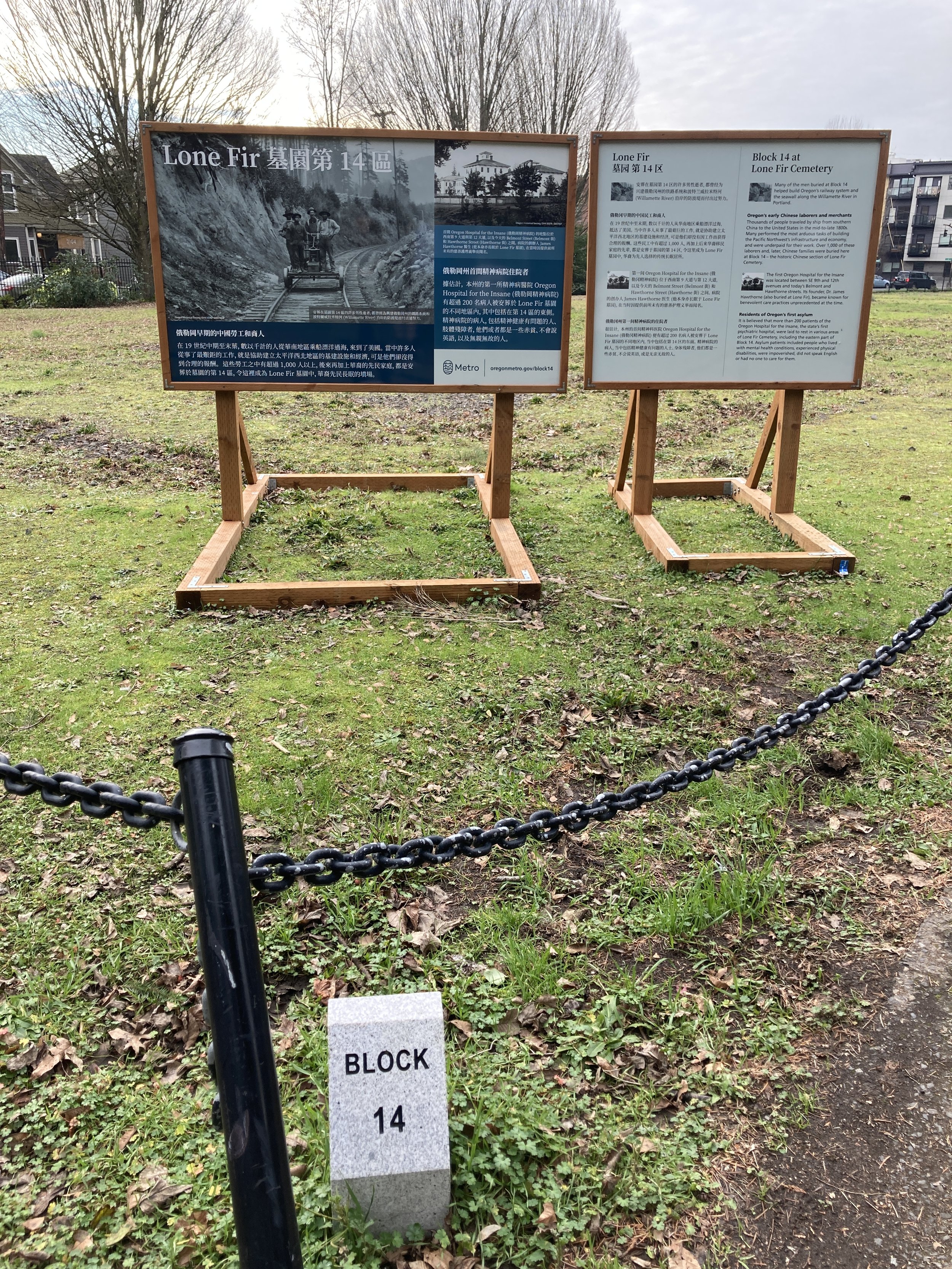

In the southwest corner of the Lone Fir Cemetery you’ll find a neglected 1.25 acre plot that has no gravestones or memorial markers of any kind. It’s litter, rocks, grass, weeds, a handful of shrubs and trees, three small engraved granite slabs that indicate the block number (one in each corner that faces in to the beautiful parts of the cemetery) and two wooden signs which will tell you that this ugly piece of land separated from the rest of the cemetery by a thick black chain is the historic Chinese section of Lone Fir Cemetery.

The History of Block 14

Chinese people have been in Portland since 1850 and were integral in the building of this city. They performed some of the most physically demanding work in the region: building railroads, mining, and building Portland’s seawall and the original sewer system. They removed stumps from prospective roads after trees were cut, chopped firewood, ran laundries, and grew produce for the entire town.

In 1875, the Page Act effectively prohibited the entry of Chinese women to the United States. Specifically, the law prohibited the entry of "forced laborers", but was heavily enforced against Chinese women seeking entry because of the assumption that all Chinese women seeking entry to the United States would engage in sex work.

In the early 1880s, Chinese Americans made up approximately 10% of the City of Portland.

In 1882, the Exclusion Era began with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act. This federal law banned Chinese laborers, both skilled and unskilled, from entering the country, prohibited Chinese immigrants from becoming US citizens, restricted the movement of Chinese people already living in America, and was the only US law to ban immigration of a group of people on the basis of race. The act was not repealed until 1943, at which time only 105 Chinese immigrants were allowed into the country per year, and this limit was not repealed until 1965.

In the late 1860s, prior to the Page Act and the Exclusion Act, the first Chinese person was buried here in the Lone Fir Cemetery.

Between 1891 and 1928, around 2,500 Chinese sojourners and settlers were buried in Block 14 of the Lone Fir Cemetery. According to Chinese custom, Chinese people who died overseas were buried for a short time, and then their bones were dug up and returned to China to be reunited with their ancestors. Most of the Chinese people buried in Block 14 were laborers; many were men who helped build Oregon’s railway system. Others were women and children, although this was relatively rare. In the county’s burial records, many are unnamed, listed simply as “Chinaman.”

In 1917, the Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) oversaw the first major disinterment at Block 14, and as per custom, the remains of approximately 500 people were returned to China. In 1948, at the request of Multnomah County, the second major disinterment occurred, and approximately 260 people’s remains were sent home.

In 1948, during the time when only 105 Chinese people were being allowed into America every year, Multnomah County set its sights on this land for use as a maintenance yard for the highway department. In keeping with the general sentiment of the time regarding Chinese people, Multnomah County built a facilities-service building and a parking lot on Block 14 in 1952.

50 odd years later, in 2004, Multnomah County planned to sell this property to a developer. A broad constituency of individuals and organizations objected, protesting that intact burials might well exist beneath the asphalt. In January 2005, a team of archaeologists found two intact burials. At this point, it became clear that this land could not be sold for commercial development, and the County recognized its duty to remove the building and include the site with the rest of Lone Fir Cemetery. Thus, in 2007, the building was removed, the ground leveled, and the block was deeded over to Metro and incorporated back into the Lone Fir Cemetery.

In 2008 Metro consulted with individuals and community organizations germane to the demographic impacted by the forgotten burials, and had plans made for a Cultural Heritage and Healing Garden at Block 14. However, at that time there was no money to build the garden, so the project stalled with the plans drawn but no start date. It was during that time that the Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation came to life, due to the combined efforts of the CCBA, the Buckman Community Association, and others to fundraise the money needed to build the promised garden. Although the Foundation did raise funds, they were not enough to cover the millions of dollars needed for the project, and Block 14 continued to languish.

A few years after Metro was deeded the property and the plans were drawn up, a sign was erected at Block 14 that outlined a brief history of the space (see above photo). The sign didn’t stop people from disrespecting the site, however; Block 14 has long been used as a place to recreate, a convenient litter haven, and a destination for folks taking their dogs out to do their business.

In 2019 voters approved the Parks and Nature bond, which meant there was finally money put aside for improvements at the Lone Fir Cemetery. However, there was no line item designated specifically for the long-awaited Cultural Heritage and Healing Garden, and it took one full year for the Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation to get that line item put in. Finally, in 2020, it was looking like there was forward momentum for the Memorial Garden in Block 14….but as we all know, 2020 had other plans for us.

May 16, 2023

I am still working on this section of my site, as I have yet to talk about the 185 patients from the Hawthorne Asylum that are buried throughout Lone Fir Cemetery, including 54 documented burials in Block 10. The Cultural Heritage and Healing Garden will also be in honor of the asylum patients.

Becoming an Artist in Residence

I first became acquainted with Block 14 by the same sign that remains there to this day. A frequent visitor to cemeteries since my teen years and a Funeral Celebrant for over a decade, I am naturally drawn to cemeteries and consider memorialization and remembrance both an honor and an art. When I read the sign at Block 14 during my first visit to Lone Fir Cemetery, I was surprised to learn the history and saddened by the sorry state of the site, which felt so barren and unloved in comparison with the rest of the cemetery. At that moment, I decided to keep an eye on Block 14.

A couple of years later, I was still visiting the cemetery and still seeing the same empty lot. Sometimes during my visits I would run across people using Block 14 as a dog park or recreational field, and each time, I would educate folks about the space and gently ask them to respect the ancestors buried there. Finally, during the pandemic when Portlanders (including me) were spending loads of time outdoors anywhere they could, I got fed up with watching people disrespect the space, and tired of waiting for something good to happen there. I began to hatch an idea of creating onsite events and art that would show people that the space was being actively cared for, while educating the public about the history of Block 14.

Socially engaged art is nothing new to me; I’ve been doing it since 2004 when I began working in “low income” housing as a resident services coordinator and using my arts background to engage with the vast diversity of people I served in those housing complexes. I love to listen and learn in whatever space I’m in, and Block 14 provides a natural entry into conversations around erasure and marginalization, grief and healing, and the intersections of mental health, race, gender, and class. Furthermore, Block 14 is near to my heart because my own ancestors came from China to Hawai’i around the same time that the Chinese sojourners buried in Block 14 came to Oregon, and also because at the time I became involved with the site it was thought that around 200 insane asylum patients could potentially be buried in Block 14, and I myself live with mental illness. Block 14 felt like an apt fit for my particular skill set and experience.

Early in 2022, while it was still cold and wet here in the Pacific Northwest, I went to Block 14 with intention. Lunar New Year was coming up in February, and that seemed like the perfect time to launch what I had decided would be an artist residency in the space.

I started by creating a labyrinth in the center of the site, using only the loose rubble from the demolished building and parking lot as my materials. I timed my construction so that the labyrinth would be ready in time for Lunar New Year, and used each labyrinth-building visit to Block 14 as a chance to post on Instagram and invite the public to learn more and get involved. You can learn all about that process and see photos here. Please note that due to recent findings regarding remains at the site, I will be removing the labyrinth and creating a new ephemeral work in the space that does not rest upon ground that may still contain ancestors.

Then, on Lunar New Year, myself and some volunteers decorated the perimeter of Block 14 (see above pictures).

Building the labyrinth, decorating for Lunar New Year, and regular posting on Instagram got the attention of the folks at Metro as well as the Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation. The attention was not entirely favorable, however; remember, I hadn’t asked for permission to create the labyrinth, and some of my Instagram posts were highlighting the racist history of the site, calling Metro out for some language they’d used in an interview about the site, and also challenging the big black chain around Block 14, which made it inaccessible for folks with mobility issues. I was bringing attention to the site, but I was also a bit of a thorn in the proverbial side.

Sometimes you have to make a bit of a ruckus to get people to notice you. I’m not advocating for doing dangerous and rash things, but I do believe that every single one of us has within us the ability to do big things with very little, and Block 14 gave me the opportunity to test this for myself. The first couple of Zoom meetings with Metro and the Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation were not exactly comfortable. At that point I was an unknown entity doing unsanctioned things at a sensitive site, and Metro and LFCF were cautious. I, too, had my reservations, as I know how bureaucracy works and I didn’t want to get tangled in its gears. I had engagement from my social media posts and all the people who were coming out to help with the labyrinth, the momentum was there to do some fantastic community events, and I felt determined to keep going at Block 14.

It took some time for Metro, the Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation, and I to find our groove and build trust. Metro is a behemoth, and Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation has strong ties to the Oregon Consolidated Chinese Benevolent Association, so I had to tread carefully. Block 14 was, among other things, an opportunity for me to learn more about my Chinese cultural heritage, but in the initial stages of getting to know all the players in the game, my lack of knowledge could easily leave me wrong-footed, as Chinese traditions are both deep and wide, and those who uphold them can be unwavering. Thankfully, all of us were able to give a little bit at just the right moments, and I was not only able to continue with the labyrinth, but bring another of my 2022 goals to fruition by hosting Lone Fir Cemetery’s First Annual Qingming Festival in partnership with the Lone Fir Cemetery Foundation.

Present Day at Block 14

In the beginning of my residency at Block 14, I split my time between building the labyrinth and days spent in research, learning about other Chinese cemeteries in the PNW, following the trail of breadcrumbs in an attempt to figure out where the people from the Asylum were buried, and educating myself about the racist history of our nation and the state of Oregon so I could understand just how an injustice like Block 14 could have happened. Since I began to look after Block 14, more remains have been found, Metro has funded the effort to memorialize the history of Block 14 through the 2019 Parks and Nature Bond, and after many years and much effort, the Cultural Heritage and Healing Garden will finally begin to take shape in 2025. These days, it’s all about continuing to educate the public through outreach and events, as well as helping to guide the process of creating the Cultural Heritage and Healing Garden through workgroups with Metro and Knot, the landscape architect firm hired to design the garden. I am still the Artist in Residence, and I hope to be artistically involved with Block 14 right up to the moment that the ribbon is cut at the new Cultural Heritage and Healing Garden.

Springtime Blooms

In all but the coldest and rainiest seasons I spend at least a few hours a month at the cemetery. The land is especially beautiful in the springtime, and there are many plants that flourish there before the landscapers come and mow them down.

Offerings

Oftentimes I find small offerings left at Block 14, and these I photograph and, if needed, take home and burn. I burn the offerings at home because Metro does not allow burning at the cemetery, nor do they allow anything other than flowers to be left on graves. This includes mementos, photos, stuffed animals, vases, toys, lawn ornaments and lawn lights.

Dig Through My Research Troves

My practice usually involves quite a bit of research, but Block 14 and the events that spun out of it (Qingming and Hungry Ghost Festival) have by far been the most research-intensive of all of the projects I’ve undertaken. I spent countless hours combing the internet to find everything I needed to read, and I don’t want anyone to have to go through that again, so in addition to the links embedded in the text of the Block 14 page, here is a good jumping off point for folks who are interested:

Chinese Death and Cemetery Ritual

Feng Shui and Chinese Rituals of Death across the Oregon Landscape

To Religious Chinese, Cemeteries Are of Grave Importance

History of Chinese farmers in Portland

The Farmers of Tanner Creek: The little-known history of Chinese farmers and vegetable peddlers in Portland. Oregon Humanities

History of Chinese people in Oregon

Passage of the Chinese Bill A news article from the Willamette Farmer regarding the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882

Stories of the history of Chinese people across Oregon hosted by Portland Chinatown Museum, videos

Chinese Americans in Oregon Oregon Encyclopedia, covers 1850 - 2000s

Workers of the Central and Union Pacific Railroad

Next generations tell the buried tales of Chinese Northwesterners Seattle Times/Pacific NW Magazine

Bitter Harvest - Chinese farm workers helped Oregon establish its reputation as an international beer capital. Oregon Humanities

History of Chinese people in the United States

History of Chinese Americans https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Chinese_Americans

Burlingame Treaty 1868 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burlingame_Treaty

Page Act of 1875 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Page_Act_of_1875

Angell Treaty of 1880 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Angell_Treaty_of_1880

Chinese Exclusion Act 1882 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_Exclusion_Act

Scott Act (1888) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scott_Act_(1888)

Library of Congress Chinese immigration history

Articles Regarding Block 14

Roots Entwined: Archaeology of an Urban Chinese American Cemetery This fascinating article is specific to archeological findings at Block 14. It’s on JSTOR so you’ll have to create a free profile to read it, but it’s worth your time.

Plans for the cultural heritage and healing garden at Lone Fir Cemetery

Block 14 at Portland’s Lone Fir Cemetery will finally get its due Street Roots 2021

They were paved over and forgotten for decades. Now a cemetery garden will honor Chinese workers buried in SE Portland The Oregonian 2021

Metro Project Uncovers History At Cemeteries Ahead Of Suffrage Anniversary OPB, 2019 (this is the one with the “reclaim” language)

The Ghosts of Lone Fir Cemetery Portland Mercury 2009

In 2004, Portland Abandoned Plans to Develop an Old Graveyard After Learning People Were Still Buried There…The exciting conclusion of…Has a cemetery ever been sold to a developer? Willamette Week, 2008

How Portland and Oregon have historically dealt with mental illness

Beyond the Cuckoo’s Nest: How Portland and Oregon Have Historically Dealt with Mental Illness—and What It Means for Us Today Portland Mercury 2016

The Lone Fir Cemetery and the Asylum Patients of Dr. James C. Hawthorne. A brief history on the origins of mental health care in Oregon, followed by detailed maps of the Lone Fir Cemetery and the burial sites associated with patients from the asylum.

Persons Buried in Lone Fir Cemetery, Portland, Oregon Who Were Sent Over From Dr. Hawthorne’s Insane Asylum from 1867–1879. A brief history of the asylum followed by what may be an exhaustive list of patients buried in the cemetery.

Mental Health PDX: Mental Health Association Of Portland

Salem Pioneer Cemetery

2017 newspaper article about the rediscovery of a Chinese shrine at the Salem Pioneer Cemetery

The Chinese shrine at the Salem Pioneer Cemetery - a case study

PSU history dept. article about the shrine

Salem’s Qingming Festival